Cell receptor involved in autoimmune diseases?

P2Y10 receptor promotes migration of CD4 T lymphocytes

An important part of the immune defence is the migration of leukocytes to the site of the inflammatory stimulus. This is mediated by chemical messengers whose counterparts are receptors on the surface of the immune cells. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research have now investigated the role of a G protein-coupled receptor called P2Y10 in CD4 T cells. Mice lacking this receptor show less pronounced autoimmune responses in the experiment. The study shows that P2Y10 could play a role in neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis or other autoimmune diseases.

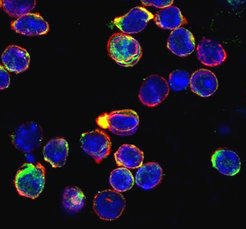

The therapy of autoimmune diseases is complicated by the fact that the underlying processes are often not fully understood. In many cases, the trigger is likely to be a defective or excessive immune defence. Part of this immune defence are the leukocytes. There are different types of cells that perform different tasks. Scientists from Nina Wettschureck's research group at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research in Bad Nauheim became aware of one group of leukocytes, so-called T helper cells or CD4 T cells, when they analysed the expression of G protein-coupled receptors on different cell types. "We found that a representative of these receptors, P2Y10, was particularly abundant on T helper cells from the spinal cord," said Malarvizhi Gurusamy, first author of the study.

T cells are attracted to the site of inflammation by chemical messengers. This migration is controlled by various receptors, many of them G-protein-coupled receptors. "The observation was made interesting by the fact that the functioning of P2Y10 has not yet been sufficiently clarified," Gurusamy said.

To get to the bottom of this, the Max Planck researchers first switched off the P2Y10 gene on T helper cells in mice. They then compared the properties of T-helper cells in the P2Y10 knockout mice with those of control animals.

While T-cell activation, cell growth as well as cell differentiation were unchanged, T-helper cells lacking the P2Y10 receptor showed reduced migratory behaviour. "We examined a number of messengers and found that T cells without the P2Y10 receptor migrated more slowly and, compared to the control group, a larger proportion of cells did not respond to the chemical stimulus at all," the researcher explained.

In an animal model in which inflammation of the nervous system is experimentally induced, the lower migratory activity of P2Y10 knockout cells resulted in fewer T helper cells migrating into the spinal cord and a lower overall inflammatory response. This could be an indication of the receptor's involvement in autoimmune diseases.

In further experiments, the Bad Nauheim researchers therefore investigated the molecular details. According to this, P2Y10 controls the migration behaviour of the T-helper cells via an auto-paracrine feedback chain. This means that migration is influenced both by factors in the environment of the cells and by the cells themselves. Certain lipids and nucleotides play an important role here.

"We were also able to show that P2Y10 also regulates the migration behaviour of T helper cells outside the central nervous system, for example in the case of inflammation of the skin," said Wettschureck. "Our study indicates that P2Y10 could play an important role in various autoimmune diseases." For this reason, the next step will be to investigate by means of a pharmacological study whether P2Y10 could represent a starting point for a therapeutic approach.